The famed ‘Tesco’s bag’ remains one of the few shore species capable of pulling your rod over. Even a baby bag – a 5lb thornback ray – will test your rod-rest stability as it picks up the bait and flaps like fury over the sea bed.

Ray do fight – or should it be described as kiting because it uses its wide body to work the tide like a kite does the wind? You might turn up your nose at the fish but don’t scoff until you have seen a ray’s wings surface 100 yards out or experienced a fish toughing it out and staying deep. This is the stuff angling dreams are made of.

My ray fishing experiences were limited – there are not a lot of ray around the Kent coast – until I travelled to the Isle of Wight in the 60s and fished an all-night Readers SAC open. It was June and the small-eyed ray were prolific from the Chale and Atherfield beaches.

I remember it as if it were yesterday. I fished under Blackgang Chine and landed 30lb of small-eyed and spotted ray on frozen sandeels in a mad dawn hour and have been hooked on ray ever since.

These days fewer small-eyed, thornback or spotted ray are caught from the Solent shores or the rest of great Britain for that matter, but there are still enough to make them a worthwhile target from spring and through the summer.

My best catches have come from the rugged coast of County Clare on Ireland’s west coast. The clear water of the Atlantic Ocean supports a consistent inshore population of ray safe from the nets in the kelp and mixed ground.

Thornback are most common, but the rarer types, like the cuckoo, undulate and blonde, turn up on occasions.

Only last year I lost a possible big blonde ray that I could only coax towards the shore but not lift off the sea bed. As a consequence it buried itself in the kelp and was lost. In the past I have landed three thornback on a rig aimed at dogfish and only last year I recorded a double hit of 7lb thornback. Incidentally, mine are always returned.

HABITAT AND TACTICS

You would expect ray to be completely at home on a flat sea bed. Indeed their design suits an even silty or sandy sea bed where they can partially bury themselves in wait for their prey.

Ray are also commonly found in kelp or over sandy patches between reefs and weed, especially in Ireland. Another ray hot spot is the back or deepening side of a sand bar where their shape and fin control allows them to feed at various depths on sandeels, crabs and other marine creatures.

They are also found close to and within many estuaries, especially the thornbacks and sting ray, who enter even small estuaries in spring to feed on the peeling shore crabs.

The species, especially thornbacks, tend to shoal tightly and are particularly vulnerable to commercial nets as well as rod and line. Hook one and you will invariably catch another, which is one reason why their numbers have become so depleted.

In recent seasons thornbacks have enjoyed spawning successes and remains fairly prolific in some regions, including the north-east coast and Irish west coast. Scotland, Wales, the Bristol Channel, Solent and waters into the West Country also get their share of fish.

The hot time for ray is around dusk, during darkness or dawn. They can be caught during daylight from many silty estuaries, while in the deep water of the western Irish coast they are caught in clear water, sometimes very shallow water.

Ray bites generally start with a small flutter of the rod tip as the fish more of less flops over the bait. Once the bait is engulfed the fish will move off powerfully, often pulling the rod over hard, so make sure your rest is secure or you are holding the rod.

ON YOUR MARKS

Most regions of the Atlantic coast and most of the Irish Sea hold ray in summer. Ireland’s western coast with its mix of rocks, estuaries and sweeping sandy bays is a very consistent venue.

The southern side of the Lleyn Peninsula in west Wales is a recognised venue, as are both the Welsh and English sides of the Bristol Channel, where the hot spots include the beaches between Porlock and Weston.

South-west Scotland gets its share of thornbacks in the Solway Firth. Through the English Channel they peak in the Solent, but become rare from the shore through Sussex and Kent, but catching one is not impossible.

Essex rivers, like the Blackwater and Crouch, still produce ray in spring with St Osyth still favourite for a big sting ray.

Beaches above the Wash, especially between Skegness in Lincolnshire and Hornsea in South Yorkshire, all produce thornbacks through the summer months.

BEWARE OF THE SPIKES

BEWARE OF THE SPIKES

The ray’s powerful jaws mean you should remove hooks with care or use forceps. Another danger are the spikes and prickles all over their body which are razor sharp.

Even the dull-looking painted ray’s tiny spines can draw blood if the fish is handled roughly. Grip either side of the nose with a cloth or around the tail, but not with bare hands.

Sting ray should not be handled and never stand on them because the venomous spine on the tail can whip over their head and penetrate rubber.

TOP BAITS AND RIGS

My top ray bait is a frozen sandeel. There is no argument about that. Ray will also take live or fresh sandeels, which is especially deadly afloat. The species are also partial to peeler crabs and hermit crabs in most estuaries during spring, and even hard-backed crabs aren’t safe.

They gobble up fish baits like mackerel and herring and are not averse to getting their gums around a helping of ragworms, lugworms or even squid.

Being bottom feeders they drop on the bait, smothering it and for that reason spiky wire grip leads can be a turn off, especially for the bigger fish. Skate anglers never, ever use wired sinker. It matters less from the shore, although it may be wise to use a long snood to keep bait away from the grip wires.

Ray have no teeth as such, rather bony plates they use to crush their usual food of crabs, shellfish etc. This can damage line and fingers if you let them, so the use of at least 30lb hook snoods is advised.

Hook type too is pretty crucial with a long-shank Aberdeen the easiest to remove.

A size 3/0 Kamasan B940 is ideal and particularly suited to baiting with a six inch frozen sandeel.

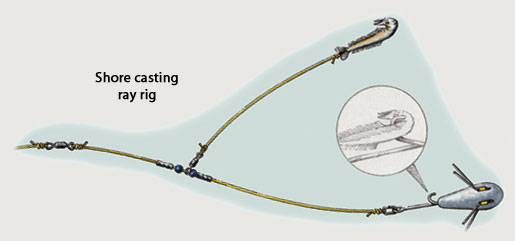

Ray are rarely very close to the shore, so a single clipped-down paternoster is easily the most efficient rig.

RAY LIFE CYCLE

Ray are a close relative of the shark and have evolved to live on the sea bed. It has a shark-like cartilaginous skeleton. There is no biological distinction between skate and ray, although those with long pointed snouts are called skate and those with short or rounded snouts, ray.

Confusion has arisen because of the difficulty in deciding if the snout is rounded or pointed, thus thornback ray are often called skate.

The ray is responsible for the mermaid’s purses, which are the egg cases laid by the females. These oblong, dark egg cases have a long horn at each corner.

Only sting ray and electric ray give birth to live young, like other members of the shark and ray family.

Ray mature fairly late with a female unable to reproduce until around nine-years-old, which explains why they are becoming scarce and why angling should put them on the catch and return list.

MEET THE RAY FAMILY…

There are 12 rays more or less common to British waters, some are only caught from the boat.

Thornback ray

The most common and the most likely ray to be landed from the shore is the thornback, also commercially called roker. Identified by the many thorns on its mottled back and the cream underside, while most other ray only have thorns or prickles along the tail or midline.

Large thornback ray, those over 20lb, are very rare and the British record of 31lb is going to be hard to beat. In the past big thornback have been recorded, but it is thought these where mostly wrongly identified white or common skate.

Small-eyed ray

Still fairly common through the southern and central parts of the English Channel.

This ray has smaller eyes than the others and is sometimes called a painted ray as is the undulate ray, hence some confusion. Boat record is 17lb 8oz off Watchet, Somerset.

Spotted ray

Spotted ray

Small species found along the English Channel, Irish Sea and Atlantic coastlines of Ireland. Rarely beats 5lb with the British shore record at 8lb 10oz from Whitsands Bay, Cornwall.

Undulate ray

Its undulating dark patterns edged with white spots make it the prettiest of all the small ray. The markings are more distinct than those of the painted ray, which has pale cream markings and no white spots. Rare from the shore except from the Irish west coast.

Cuckoo ray

Cuckoo ray

Distinct yellow and black eye spots on the upper side of the wings mark this as a rare catch. Most common in the south, but has been caught all around Britain at depths between 20m and 150m.

Blonde ray

Very rare from the shore, this large ray is a species mostly associated with boat fishing, although it has been caught from the rugged western coast of Ireland. Said to be extending its range due to global warming.

Electric ray

Very rarely caught, but nevertheless there is a British rod-caught record of 90lb 1oz for the species caught off Dodman Point in Cornwall.

Common skate

There are three species, common, white and long-nosed. Monster fish reach well over 100lb in weight and are still landed by boat anglers in deep Irish and Scottish waters where they are returned, indeed in Ireland they are a protected species.

There are places you may have a chance of hooking one from the shore, including Loch Raig on the Isle of Lewis where the British Record shore of 169lb was landed in 1994. In Ireland Fenit Pier has produced a few.

An angling friend of mine once likened landing one to pulling a grand piano up a cliff.