Carved out of numerous rocky juts and indentations, the Muchalls shoreline brims with obvious cod potential. Having never fished the stretch before, it’s a place that has intrigued me for many years.

An old friend, who hung up his shore poles long ago, used to recount tales of hardy cod anglers streaming off the steam train at Muchalls and heading for the nearby rock marks.

“The catches made on primitive tackle and baits were usually enough to keep families in fresh white fish for days,” he used to say. Sadly, the railway station is no longer there and the standard of North Sea cod fishing has disappeared down its own plughole in the most recent decades.

The one bright light is that these indomitable rocks are a constant and there is no reason why decent numbers of cod, by today’s standards, shouldn’t be caught here.

I could see no reason why the area wouldn’t produce fish in the modern era, but my curiosity has always niggled as to why there is little mention of Muchalls among the regular cod-roving fraternity. Could it be well guarded a secret? Or, maybe, there was an downside to the place? Maybe it was time for Souter to investigate.

Cod fishing in Scotland’s north-east had been indifferent in the days and weeks leading up to my weekend visit. Our band of five adventurers weren’t exactly bursting with ideas; my suggestion to give Muchalls a bash met with no objections, probably because they didn’t have any ideas either.

In keeping with many such coastal settlements, the charming surrounds of Muchalls and its rocky outward crust are steeped in sinister history.

Stories of smugglers’ warrens and ghostly phantoms abound, but, for all that, Scotland’s most famous bard, Robert Burns, once described Muchalls as “a good deal romantic.”

If first impressions count for anything, it is difficult to disagree with the man whom I hold responsible for my annual intake of a sheep’s stomach stuffed with minced offal and spiced meal.

The race is on

Muchallsis an expansive area and I had no directions to any specific marks. Views of the shore edge from the high cliffs at the northern end of the venue are a sight to behold. Landmarks with captivating names, like Grim Brigs and Brown Jewel, adorn the maps.

If the names on paper prick the attention, seeing the area for real is something else. There is a savage splendour to the broth of raw rock features greeting the unsuspecting eye.

Various little rock islands that oozed cod potential caught our attention. These were lapped and, in some cases, surrounded by the incoming tide. An isolated sea stack, known as the Old Man of Muchalls, stood out to the right, while rock-strewn basins cut into the shore either side of lumping great hillock directly in front of us.

The place was a scatter of choices, most which I would later come to rue passing over. The grass is always greener they say and, after a brief inspection of all before us, we decided to head for an obvious point that protruded well out to sea about a mile in the distance. Getting there wasn’t a walk in the park, especially when carrying rod holdalls and rucksacks stuffed with lead weights.

Five of us yomped for 25 minutes across several fields, creaky stiles, dry stone dykes, streams and footbridges. We had no prior experience of the area, so this was a simple case of following our noses towards the sea.

The sweaty toil aside, it wasn’t an unpleasant trail in the sun, but the killer irony here is that I later discovered we could have deviated down an alternative quiet track and parked up a couple of hundred yards from Doonie Point, which I later discovered was the obvious mark we were heading for.

Cresting the last rise, we were again greeted by the rough shoreline. We had emerged only a short distance from the point and access to it looked straightforward. It was then I spotted two anglers cutting across the field to our right; they had spotted us too and were now galloping towards the mark ahead of us.

You realise there was a much shorter route – the sea angling party pause at a footbridge over a stream during their route march

Room for two

Unlike us, Craig Dempsey and John Osinski, from Fife, the newcomers, had fished here before. They knew that space was at a premium and that first to reach the mark would claim the prime spots.

John was off like a shot, scurrying over rocks and up onto the point like a proverbial rodent up a drainpipe. As expected the Fife lads commandeered the point, and with no Plan B up our sleeves, we split up.

I won’t spout bull about using skill and watercraft to pick a likely spot because the truth had more to do with beggars, choosers and necessity.

The flood was an hour-and-half old and was already forming a wide trough that snaked behind us. Stan Eggie and his fishing-mad grandson opted for the safety of a higher spot several hundred metres back. With time the enemy on the lower rocks, Mark Davidson, Shaun Cumming and I gambled on a plateau of rock in front of a string of big rocks that would act as safe stepping-stones back across the rising moat of seawater when the time came to bail out.

Synchronised snagging

Lug and crab baits carefully mounted on simple single hook rotten-bottom rigs quickly winged their way seawards. However, lack of venue knowledge stung me minutes later when an attempt to strike a solid bite saw me snagged solid and lose the lot.

The fuller nature of what we were casting into became obvious when Mark and Shaun tried to wind in and found themselves locked into sea bed.

Shuffling along the rocks in the hope of identifying a less vicious tract didn’t help, while long casting or short made no difference to our tackle casualties.

With a cautious eye on the fast-filling gully behind, I caught sight of action back along at the point. John’s rod was pulled over into a healthy bend, and he was now carefully working to draw the fish ashore. Craig stood close by ready to get involved should an extra pair of hands be required.

Acodling of about 4lb broke surface and, seconds later, John dipped his rod and swung the kicking fish to hand with an assured expertise. He then hoisted a cod in the direction of three envious pairs of eyes.

John’s success was the final straw and our cue to beat a retreat. With the tide well up in the gully and our route to safety fast disappearing under water, we conceded defeat and abandoned the rock. Stan and his grandson joined us at the top of the shoreline and reported the total of a couple of coalfish from equally merciless ground that they promised never to revisit.

On the way back to the cars, we stopped to chat with John and Craig. In stark contrast to our misfortunes, it turned out they had both missed other fish and lost only a couple of lead weights. What price local knowledge?

It would be easy to be dismissive of Muchalls on the strength of this bad experience, but I won’t be throwing in the towel just yet.

I still have a hunch about the place, an infuriating itch that still needs scratching. Putting events in perspective, we learned exactly the areas of Muchalls not to fish, which I suspect is only part of the picture. I saw too many mouth-watering possibilities from where we first surveyed the shoreline to concede defeat after one bad outing.

If the opposite end of the venue that I earlier ignored comes up trumps then I’ll let you know. If not, then I’ll never mention Muchalls again.

GETTING THERE

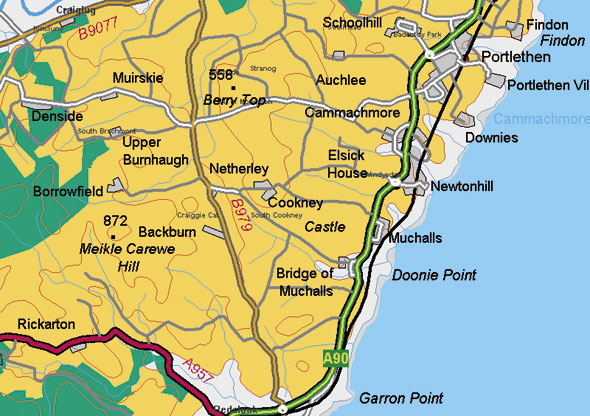

If we had paid closer attention to the map and parked at Bridge of Muchalls, rather than a full mile further back at Muchalls itself, we would have had only a short hop to Doonie Point.

Take the A90 past Stonehaven and on towards Aberdeen. Turn off at Bridge of Muchalls, which is clearly signposted on the main drag just before Muchalls.

Follow the road to the end and park carefully alongside the little cluster of stone dwellings and outbuildings.

Doonie Point is a short jaunt from here and obvious from the edge of the shore.

See Ordnance Survey Landranger map 38.