I rarely go looking for new places to fish. I live in the far west of Cornwall where the sea is always close at hand, and even before fuel prices went through the roof I never liked driving far, mostly because time spent behind the wheel is time when I could have a line in the water. I have four regular destinations: I work my way along a long run of rocky coves a mile from my house; I also fish two beaches that face south and southwest, and one that faces northwest. These four areas mean I can find an onshore breeze – or an onshore hoolie – in anything but easterlies; and right or wrong, I believe the old saying, “When the wind is in the east, that is when the fish bite least.” Another version ends, “It’s neither fit for man nor beast,” but I find it’s OK for chasing a few mackerel for supper or digging my garden; just not much use when it comes to bass fishing.

My bass outings generally cover the time from a couple of hours before first light until sunrise, because four or five times a week I spend the daylight hours in the charity shop my wife and I run, and the evenings recovering from days of lugging stuff to and from the basement, smiling at the customers all the while and reassuring them that it’s no problem to drag three gigantic pink tea sets up the stairs only to be told they’re not quite pink enough.

HINTS FOR THE HOLIDAYMAKERS

Lately I’ve developed a bit of a local reputation as a bass man, and thanks to tips passed on in our town’s tackle dealers and bookstore, holidaymaking anglers often drop into the shop. Out of politeness they pretend to browse the merchandise, but their real agenda is to pick up tips about where to try for some whoppers. Now I’m not going to whip out a map and a Sharpie and literally mark their cards. Partly this is because I don’t want to show up in a favourite spot only to find it bristling with visitors’ rods. But mostly it’s because I think the real challenge – and the real fun – for a bass angler isn’t landing the beauties, it’s finding them in the first place. There are plenty of fish that are more difficult to pull in. Giltheads and wrasse fight harder. Sea trout and mullet, even when you can see them on the feed, are trickier to tempt with a lure or a bait. Congers and pollack are more likely to dive into snags and bust off your gear on the bottom. With bass it’s less about what you do once the rod’s in your hand, more about pinpointing those magic grid references where the large ladies come to fill their tummies; and I’m going to make sure my visitors do that for themselves, with just a few pointers from me.

So how did I pick my own four happy hunting grounds? My first and most important criterion is that I like the water to be shallow. I never go boat-fishing, I can’t stand the idea of being stuck in a small vessel until the skipper decides to call it a day, I’d much rather be able to wander as I please. So how bass behave in the bottomless offshore wilderness is a closed book as far as I’m concerned. But near to the tideline I’m convinced they feed best when their backs are covered, but only just. It’s a belief I came to slowly, over the course of a lot of blanks; because when I started chasing bass 50-odd years ago I did what most young novices do, I followed the example of my elders and betters. And they seemed to spend their time scrambling out to the ends of rocky headlands where the water at their feet was deep; or standing on steeply shelving beaches and belting their baits improbable distances into the blue yonder. Shuffling along in their footsteps I caught a fair few mackerel and pollack on spinners, flatties and rays on worm and sandeel, but not a lot of bass. But the odd ones I did manage taught me a couple of lessons, albeit slowly.

First, my Tobys and German sprats delivered best when the places I wanted to try were occupied already, which meant I had to have a few chucks in the thin, snaggy water on the way out to the craggy points. I don’t remember anyone using surface plugs or soft plastics at that time, so I left a lot of metal lures on the bottom, but that was a small price to pay for some decent bass; and for the gradual realisation that the chubby ones chase their prey right into the water’s edge.

Second, my best bait caught bass often took when, even by my own uncoordinated standards, I’d made a total Horlicks of my cast. Everyone talked about aiming for the third breaker, but sometimes my gear was touching down inside the first wave. Indeed, on one memorable occasion I landed a double – my first ever – while two old chaps were laughing at me, explaining in ripe Cornish accents that the fish live in the sea, not on the sand.

HERE’S THE THEORY

As I said, it took me a while to realise that I was onto something. To begin with I accepted what the experienced anglers told me, namely that I was a jammy so-and-so. But over time I put two and two together and came up with a simple theory as to how inshore bass behave. I know it’s not strictly necessary, but I enjoy a theory. It’s more important to find a tactic that delivers the goods, but I appreciate that tactic even more if I can come up with a logical reason why it’s effective. And here’s my inshore bass theory: the big females are eating machines, slow growing creatures that need large amounts of food to put on weight. And they also need to conserve energy, wasting as few calories as possible in finding that food; which means they’re best-off hunting in the shallows, where their meals are likely to be most concentrated and easiest to grab. Look at it this way: if someone showed you two Olympic sized swimming pools and told you they each contained a thousand prawns, would you prefer to swipe your shrimping net through the pool that was full to the brim or the one where it was only ankle deep? No contest, and a bass is going to have a more leisurely time filling her guts in a place where there’s less water for her quarry to hide in. So over time I stopped searching for rocky drop-offs and steeply inclined beaches, focusing my efforts on coves where weed beds and stony outcrops break the surface, and on sand that slopes ever so gently. And guess what: not only did I have my spots to myself, I also caught a whole lot more bass.

People still come up to me on the shore to tell me I’m wasting my time, I’ll never catch anything when my lure or bait is practically on dry land, but after so many decades of experience I have enough confidence to pay them no heed. One September night I was on my beach that faces northwest.

The wave was tiny, and I like my gear to move about a bit, so I dispensed with a weight and was freelining a little mackerel, lobbing it out 20 or 30 yards, then letting it drift around in the ripple and the tide. I had my rod crooked in my elbow while I rolled a smoke when along came a headlamp. Its owner was a polite and friendly chap, but he seemed bemused. “Your bait must be in about a foot of water; isn’t it time to cast it out again?” At which point my rod lurched over as a six pounder grabbed my Joey. “Good heavens, I’ve been fishing ragworm at range, trying to get out past the sandbar. But nothing doing, maybe I should try your game next time.” I only had four baits left, but he tried it this time instead, and we each finished with a couple of decent fish from water you could have waded in wellies.

LEARN TO LOVE WEED

Besides looking for shallow water, my second pointer is to find areas where the wave and the current lead to accumulations of stuff on the tideline. The stuff that interests hungry bass is shoals of tiddlers, mackerel, crabs, dead squid and so on. But often the best clue that you’re in a likely spot is weed drifting about; because where the weed blows, there blow the things bass feast on. After a storm my marks can be coated thickly with wrack, and sometimes I pick through it, finding all manner of bass fodder: clams, dead worms and a thoroughly mixed bag of fish, which I suspect may be discards from trawlers.

So even though the weed itself is an angler’s dark cloud, it has a silver lining, because no self-respecting bass is going to miss out on an all you can eat scavenger’s buffet. And luckily, at least on my marks, the weed tends to travel along the shore in belts; so it can be impenetrable in one place, relatively clear 50 yards away. I reckon the perfect spot to put my lure or bait is right on the edge of a giant clump. Not always easy to do, especially in darkness, and I snag up and sacrifice my share of terminal tackle to Poseidon’s whiskers; but if fishing were easy, we’d call it catching.

LUMPS & BUMPS

My third and last screening device is that I want the bottom to be uneven. When I’m fishing bait on the beach, I like to know – from exploring at all states of the tide – that I’m lobbing my gear into an area where the sand is crossed by gullies or dotted with potholes. These are the little nooks where drifting bass treats build up, and where drifting bass stop off for a feed. And when I’m on the lures, I’m happiest if I can see chunks of stone sticking up and scooped out bits which at low tide will be rockpools.

As long as there’s a decent current running or a wallop of onshore weather, a lumpy-bumpy sea floor creates swirls and eddies; and these seem to concentrate the baitfish and make them easy to catch.One morning I was pottering along my run of coves a couple of hours before the dawn. The moon was almost full, and 15 yards out I could see a flat rock the size of a billiard table. When a wave rolled in my rock was submerged, when the water receded it was visible again. I fished up and down the shore for three decent bass and three schoolies. I must have made under a dozen casts to the billiard table, and they produced all six of my fish. The trick was to land my weedless soft plastic on the flat top, then allow it to be washed off by a breaker. When I was too impatient to wait for the wave and I pulled the softie from its perch, I had not a nibble, they only wanted my lure when nature delivered it. I’ve tried the same trick on the same rock four or five times since, and it’s brought me the odd fish, but nothing like that first time.

So what was happening? Was there a shoal of sandeels in a shallow pool on top of the rock, waiting to be dumped into the sea? Were loads of gobies sitting on the granite and being washed off from time to time? Had someone been sprawled on my little table eating a picnic, and abandoned delicious leftovers to the rising tide? I have no idea, and unless I’m reincarnated as a bass, I’ll never have any idea. But although I love a plausible theory, it’s a luxury: you don’t need to be able to explain everything, just to find the fishing spots that deliver.

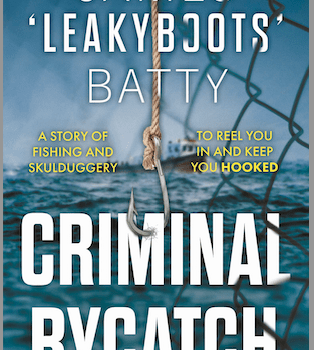

James ‘Leakyboots’ Batty is the author of “The Song of the Solitary Bass Fisher” and “Fishing from the Rock of the Bay”, both published by Merlin Unwin Books.

His new book, out in April, is “Criminal Bycatch” published by The Book Guild. It is an adventure novel set in Cornwall, which includes plenty of James’ usual humorous touches and, needless to say, plenty of fishing for bass.